Eric Steagall, a sports studies scholar in the School of History and Sociology, questions how sports can help us understand larger societal issues.

The Ph.D. candidate is researching the famous amateur golfer and Georgia Tech alum Bobby Jones, who played during the "Golden Age of American Sports" in the 1920s.

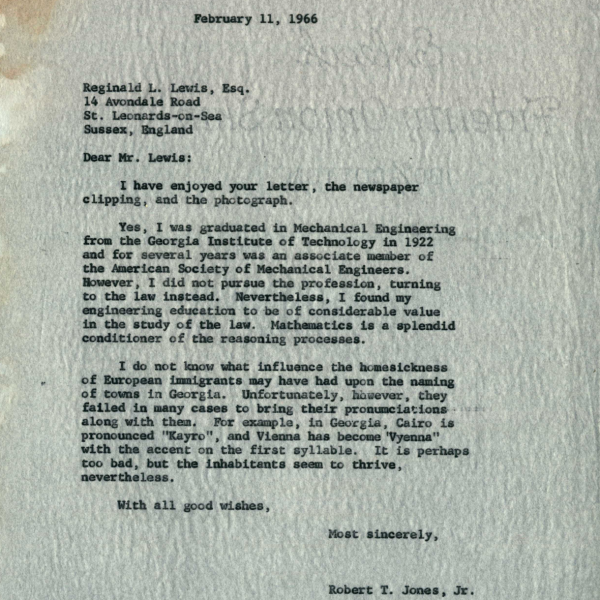

Steagall spent a week at the USGA Golf Museum and Library as the inaugural recipient of the organization's Wilson Endowed Research Fund, where he was able to explore an archive of nearly 40,000 letters Jones wrote in the later years of his life, as well as an array of niche regional golf magazines and periodicals.

In his research, Steagall looks beyond Jones' competitive career to examine the golfer’s larger role in American culture.

“Jones is portrayed as an American hero in the 1920s, but I think what has been missing is what he meant, not just to Atlanta, but to the American South,” Steagall said.

"As an amateur, people saw Jones as a bastion of tradition amidst a lot of change. He was like a breath of fresh air to a lot of people who were stuck in the past and stuck in their traditional ideas about tarnishing the purity of American culture in that time.”

Images and documents courtesy of the USGA Golf Museum and Library.

Jones as a Symbol of the 'New South'

The 1920s was just 60 years after the Civil War, and the South still lagged behind the rest of the country in most measures of progress.

Atlanta wanted to separate itself as the "New South," a city that embodied northern ideas of economic progress such as industrial diversification and urban expansion.

Jones became a symbol of that vision, Steagall said.

"Yes, he was playing golf, but it was a game first established in the U.S. by rich elite northerners. And Jones was incredibly well-educated; he was a lawyer, worked in real estate, and had many business ventures.

"So he embodied a lot of these progressive northern ideals in a way, and the Atlanta elite white boosters pounced on him as an ambassador for promoting the city to the rest of the country."

Image 1. The USGA Golf Museum and Library in Liberty Corner, New Jersey.

Image 2. Jones' 1966 letter to a friend discusses his time at Georgia Tech and how his degree in mechanical engineering helped him as a lawyer.

The Inverted Allure of Amateurism

Why is it so noteworthy that Jones was an amateur golfer?

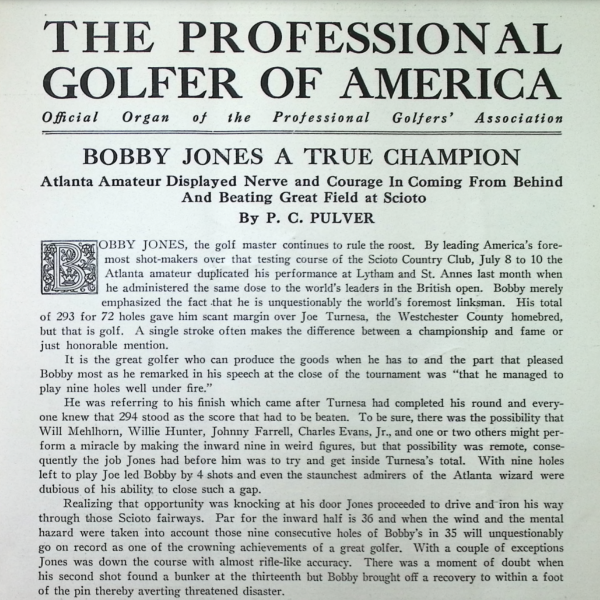

Just like today, country club sports like golf and tennis were rich and white-dominated in the 1920s. Amateurs were considered the gold standard because they had respect for tradition and ideals, while professionals were seen as tarnishing the integrity of the sport.

Image: An article describes Jones' tournament win in The Professional Golfer of America.

“There was so much change in mainstream culture and society in the 1920s, but people were still on edge after World War I. Consumer culture was growing, but there was also pushback against it.

"So discussions weren’t just around North versus South or rich versus poor, but also about commercialism, the growth of professionalism, and the rise of celebrity culture, which many associated with greed and the erosion of traditional values.”

Image: Jones plays at an exhibition match at Atlanta's East Lake Country Club in 1935.

“Sports, especially golf, are deeply intertwined in these debates from the 1920s, and Jones played a significant role in that context.

"And what’s interesting is that we're still having these conversations about amateurism today, with the Olympic model and college sports, because there's no one answer to it. There's just a lot of nuance."

Image: The Bob Jones Room at the Georgia Golf Hall of Fame.

Did you know?

Paid golfers were once so looked down upon that they weren't allowed to use the front doors at golf clubs and were banned from the locker rooms at tournaments — if they were allowed to compete at all. (The word “open” in many tournament names was originally used to note whether or not the competition was open to professionals.)

The Cost of Fame

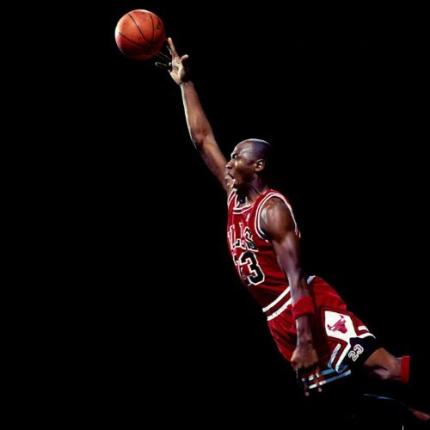

Amateur or not, Jones was the first American sports prodigy, debuting on the competitive golf scene while he was still a teenager.

He won 13 major tournaments throughout his career, and founded the Augusta National Golf Club and the Masters Tournament in retirement.

Yet, Jones referred to competitive golf as a “cage,” something he couldn't quit without letting his city down.

"Looking at Jones as a person and not just this hero is quite interesting because he hated the limelight. He was incredibly shy. And the strain of competition was so large that it was really taxing on his physical health — at each tournament, he'd lose 15 pounds from stress and throwing up.

"So it's interesting to see how, when we see these top athletes or these elite people, we only see what they choose to show in terms of their accomplishments. You don't really get to peek behind that and see what they're going through — the true costs."

Image 1. Jones as a child (center, bench) and his father (left, bench) watch a man on the 14th tee at the original East Lake golf course in Atlanta.

Image 2. Jones is lifted by fans on his return to Atlanta after winning the British Open and American Open championships in 1926.

Interested in learning more?

The Sports, Society, and Technology Program at Georgia Tech combines sports studies, science and technology, and urban studies.

It is housed in the School of History and Sociology and incorporates faculty from across the campus in public policy, international affairs, applied physiology, economics, materials science, and more.